Progressive Solemnity

Liturgy at the intersection of tradition and today.

Hymn Text Editorial Policy

If I were working on a new edition of the Hymnal, this is the editorial policy I would put in place.

1) Male-specific language shall not be used to refer to human beings in general, humanity corporately, or individual humans of unknown or otherwise unspecified gender. Specifically prohibited are the words “man” and “mankind” to refer to humanity, the words “brother(s)” and “brethren” (without their feminine counterparts) to refer to the fellowship of the church or the family of humanity, the word “son” (without “daughter”) to refer to our filial relationship with God, and the word “fathers” (without “mothers”) to refer to ancestors or forebears.

Existing hymns that use these words and phrases shall be edited to remove or expand them.

2) Male specific pronouns (“he”, “him”, “his”) for God which do not occur in direct relationship to male-specific titles (“King”, “Father”) shall be edited to neutral forms (“who”, “whom”, “whose”) or removed entirely (“God”, “God”, “God’s”) whenever doing so will not alter the meaning, rhythm, meter, or rhyme scheme of the text, provided that doing so does not create absurd or excessively awkward outcomes.

3) Male specific titles for God (“Father”, “Lord”, “King”) may be retained in existing hymns if they seem central to the hymn’s meaning, or if changing them would fundamentally alter the character of the text or the people’s relationship to it.

3a) Male specific pronouns for God may be retained in hymns that retain male titles.

3b) If the only use of a male specific title occurs in a Trinitarian formula (“Father” and “Son”), provision 3a does not apply to the rest of the text, and provision 2 should be considered.

3c) If the only use of a male specific title occurs in a Trinitarian doxology at the conclusion of a hymn, an alternate doxological formula shall be provided as an option. Poets, hymn writers, and theologians shall work together to provide feminine-language and neutral-language rhyming doxologies in a variety of hymn meters, which can be used for this purpose.

4) As often as possible, when male specific titles are retained in existing hymns, an alternate form that uses feminine titles (“Mother”, “Queen”) should be provided. These alternate forms may be provided as separate entries in the hymn book, additional/optional verses in the primary entry, or in a supplemental resource which carries the full authorization status of the primary hymnal. The most appropriate location for any feminine-language variant should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

4a) When producing feminine-language variants, female specific pronouns (“she”, “her”, “hers”) are appropriate.

4b) When simple replacement of male-specific titles with female-specific titles causes incongruities in the rhythm, meter, rhyme scheme, or meaning of the text, hymn writers, and theologians should work together to produce a more thoroughly edited variant which is both singable and sound. Those working on these texts may take the opportunity to produce texts which more fully explore the theological implications of feminine imagery.

4c) In the case of texts still under copyright, the editors shall seek permission from the rights holders and work with the original authors when possible, to produce feminine language variants. If the rights holder objects to the alteration of a text, this fact shall not preclude the original, unaltered text from appearing in the hymnal without any variants provided.

5) New hymn texts and songs which use feminine titles, images, and pronouns for God shall be sought, encouraged, and commissioned. The body of existing feminine-language hymnody shall be examined. As many as are fit for the public worship of the Church shall be included.

6) New hymn texts and songs which use gender neutral, gender ambiguous, or gender non-binary titles, images, and pronouns for God shall be sought, encouraged, and commissioned. As many as are fit for the public worship of the Church shall be included.

7) When taken altogether, the editorial choices made in response to the above provisions should result in a balance of masculine, feminine, and neutral language for God. It should not be possible for a reasonable, but theologically unsophisticated, reader to examine our hymnody and conclude that we believe God is literally male.

8) Use of “archaic” pronouns (“thee”, “thou”, “thy”) shall be retained if present in the original text and the meaning is clear to modern speakers.

8a) Texts which were previously edited to remove archaic pronouns shall be restored to their original form whenever doing so does not render them unintelligible to modern speakers.

9) Texts which, due to the evolution of pronunciation, no longer rhyme as originally intended shall be lightly edited to restore the original rhyme scheme.

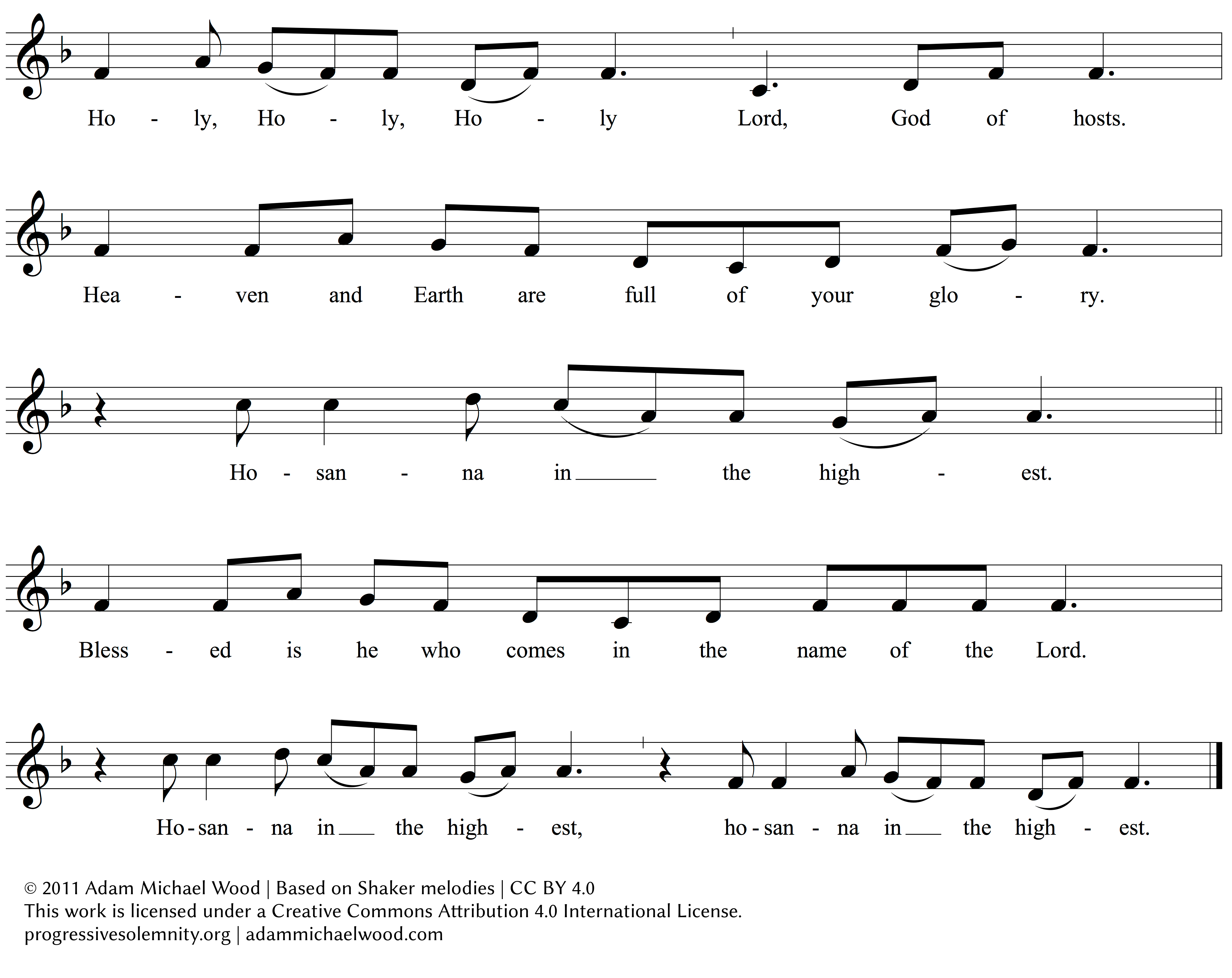

Sanctus (Holy, Holy)

See the full Mass setting here.

Audio Recording

Credits

Text

Traditional

Tune

Adam Michael Wood, based on a Shaker melody

Singers

- Br. Eckhart “Chip” Camden, OSB

- Br. Kevin Gore, AF

- Adam Michael Wood

Copyright & License

© 2015 Adam Michael Wood

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

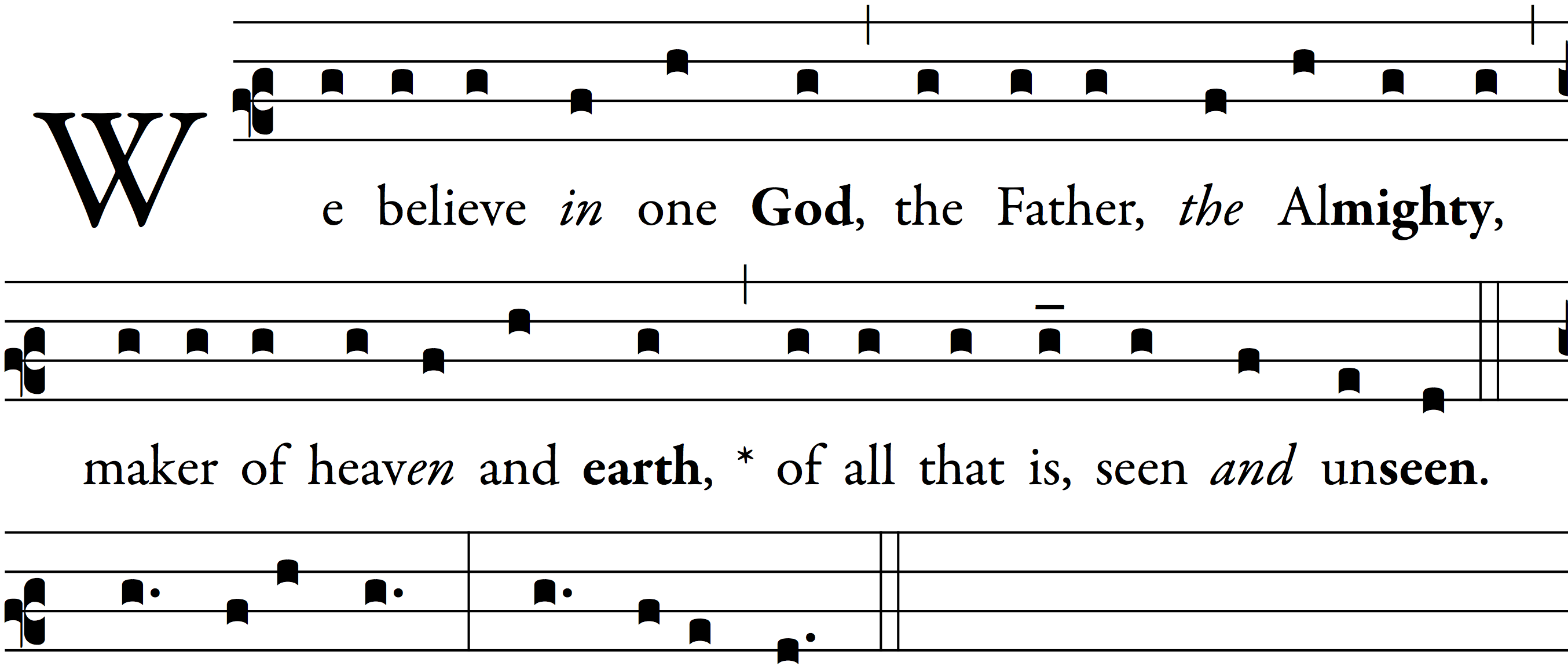

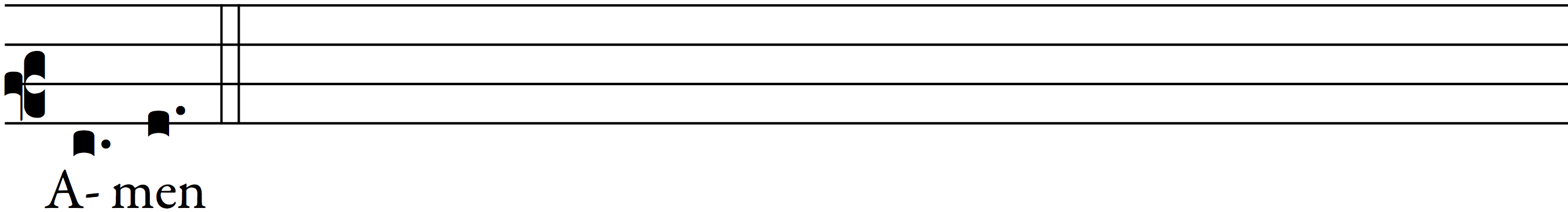

Simple Sung Creed in English

BCP (Episcopal Church) / ICET Text

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

* eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

* Through him all things were made.

For us [men] and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

* and was made man.

[ was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary ]

[ * and became truly human. ]

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

* he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

* and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead,

* and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life,

* who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

[ * who proceeds from the Father. ]

With the Father and the Son

he is worshiped and glorified.

* He has spoken through the Prophets.

[ Who with the Father and the Son ]

[ is worshiped and glorified, ]

[ * who has spoken through the Prophets. ]

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

* and the life of the world to come.

Audio Recording (BCP Text)

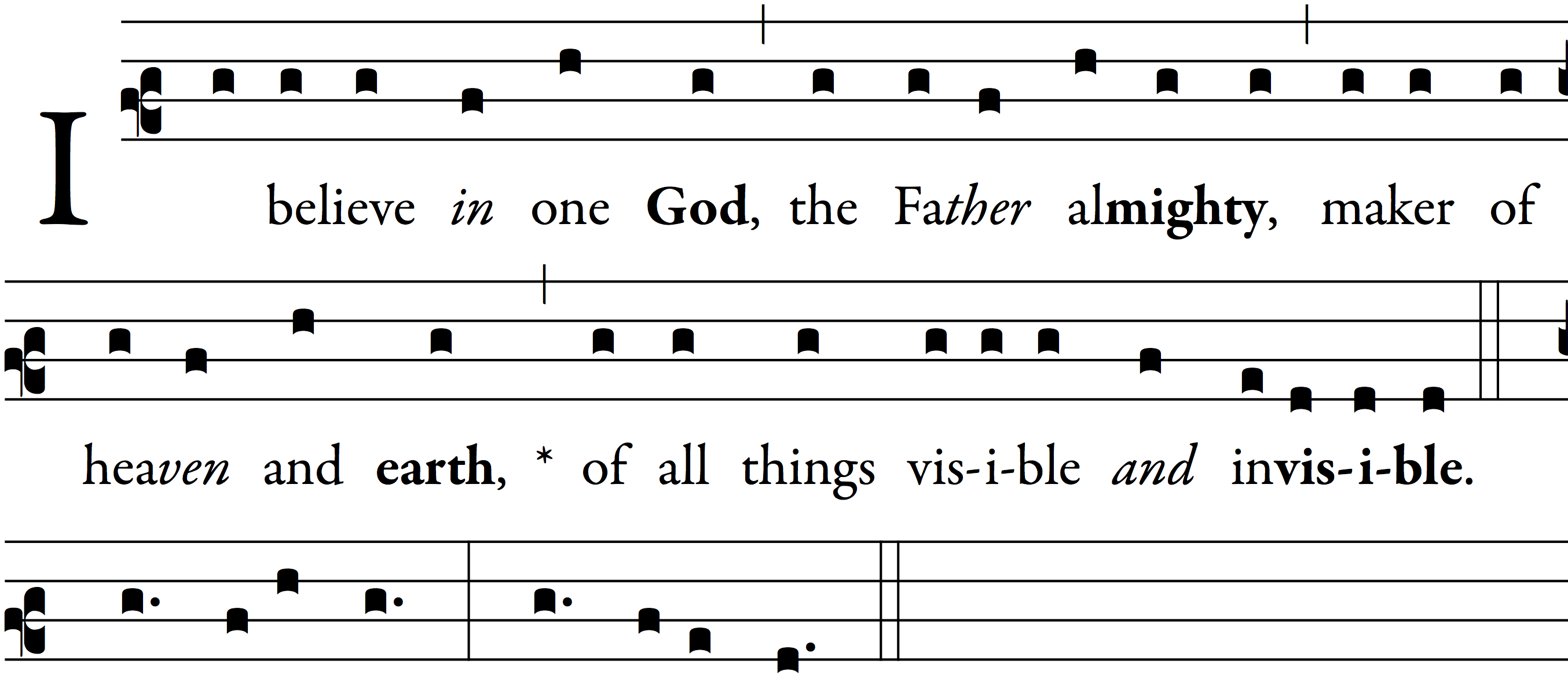

MR3 / ICEL Text

(Roman Catholic — New Translation)

I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the Only Begotten Son of God,

* born of the Father before all ages.

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

consubstantial with the Father;

* through him all things were made.

For us men and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary,

* and became man.

[ *and became– man. ]

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate,

he suffered death and was buried,

and rose again on the third day

* in accordance with the Scriptures.

He ascended into heaven

* and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead

* and his kingdom will have no end.

I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son,

who with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified,

* who has spoken through the prophets.

I believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

I confess one Baptism for the forgiveness of sins

and I look forward to the resurrection of the dead

* and the life of the world to come.

Files

Credits

Text

-

Episcopal Church Version from the 1979 Book of Common Prayer (originally translated by the International Commission on English Texts) and Enriching Our Worship I (prepared by the Standing Liturgical Commission 1997).

-

Roman Catholic version from the Third Edition of the Roman Missal, translated by the International Commission on English in the Liturgy.

Tune

Adam Michael Wood

Singers

- Br. Eckhart “Chip” Camden, OSB

- Br. Kevin Gore, AF

- Br. Brendan Williams, OSB

- Adam Michael Wood

Copyright & License

Texts

The Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church is not subject to copyright.

Enriching Our Worship is © 1998 by The Church Pension Fund (no permission needed for congregational use).

Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, International Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation. All rights reserved.

Musical Setting

© 2015 Adam Michael Wood

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

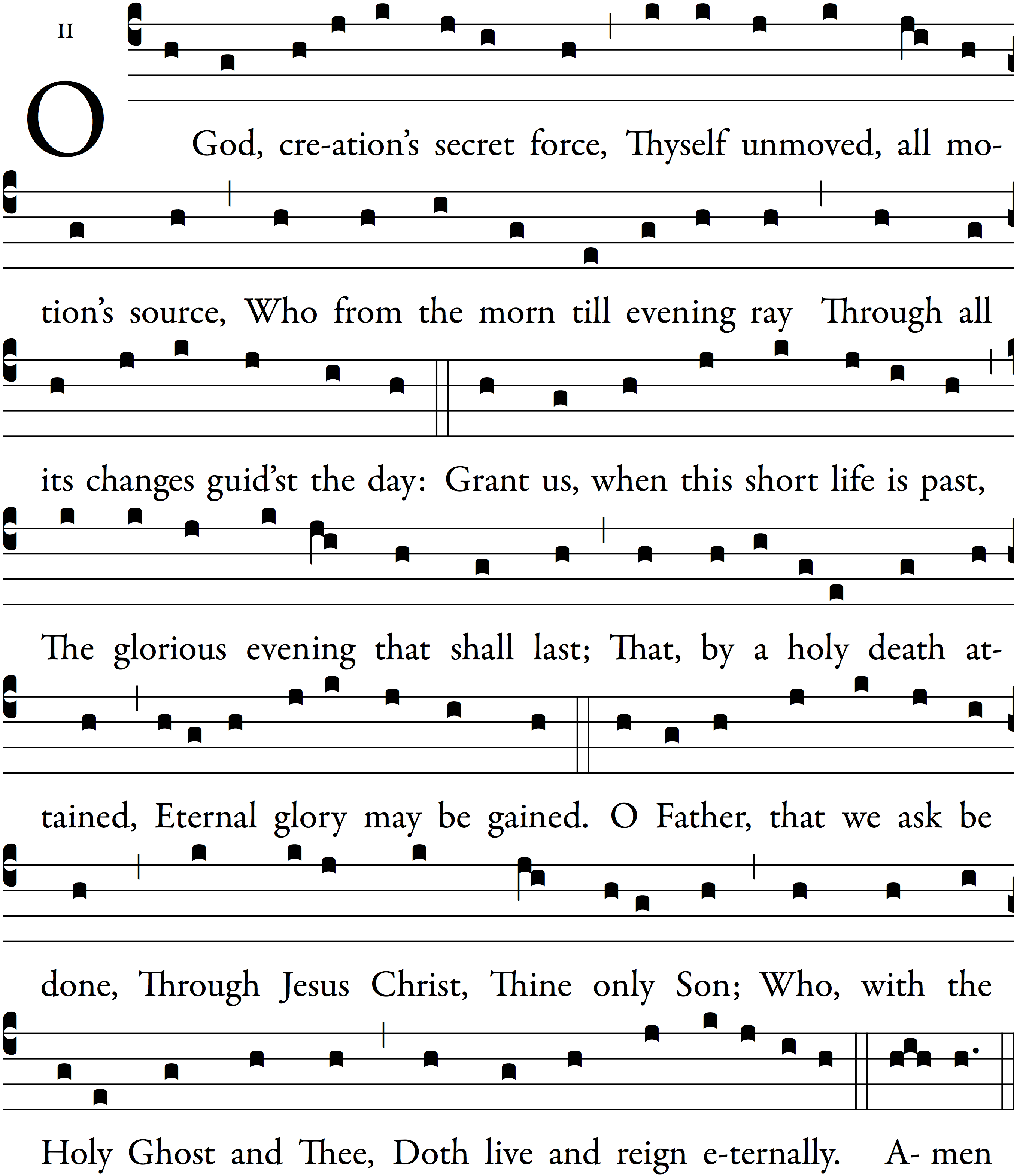

O God, Creation's Secret Force

Audio Recording

With drone and parallel organum.

File

Credits

Text

Ambrose of Milan; Trans. John Mason Neale

Tune

Traditional, from the Sarum Rite

Singers

- Br. Eckhart “Chip” Camden, OSB

- Br. Kevin Gore, AF

- Br. Brendan Williams, OSB

- Adam Michael Wood

Copyright & License

This work is in the public domain.

Compline Litany

This litany is sung nightly by the Anglican Benedictine Community of St. John Cassian. (See also their Facebook page.)

Credits

- Text adapted by Br. Brendan Williams, OSB.

- Music adapted and arranged by Br. Brendan and Matta El Meskeen.

Singers

- Br. Eckhart “Chip” Camden, OSB

- Br. Kevin Gore, AF

- Br. Brendan Williams, OSB

- Adam Michael Wood

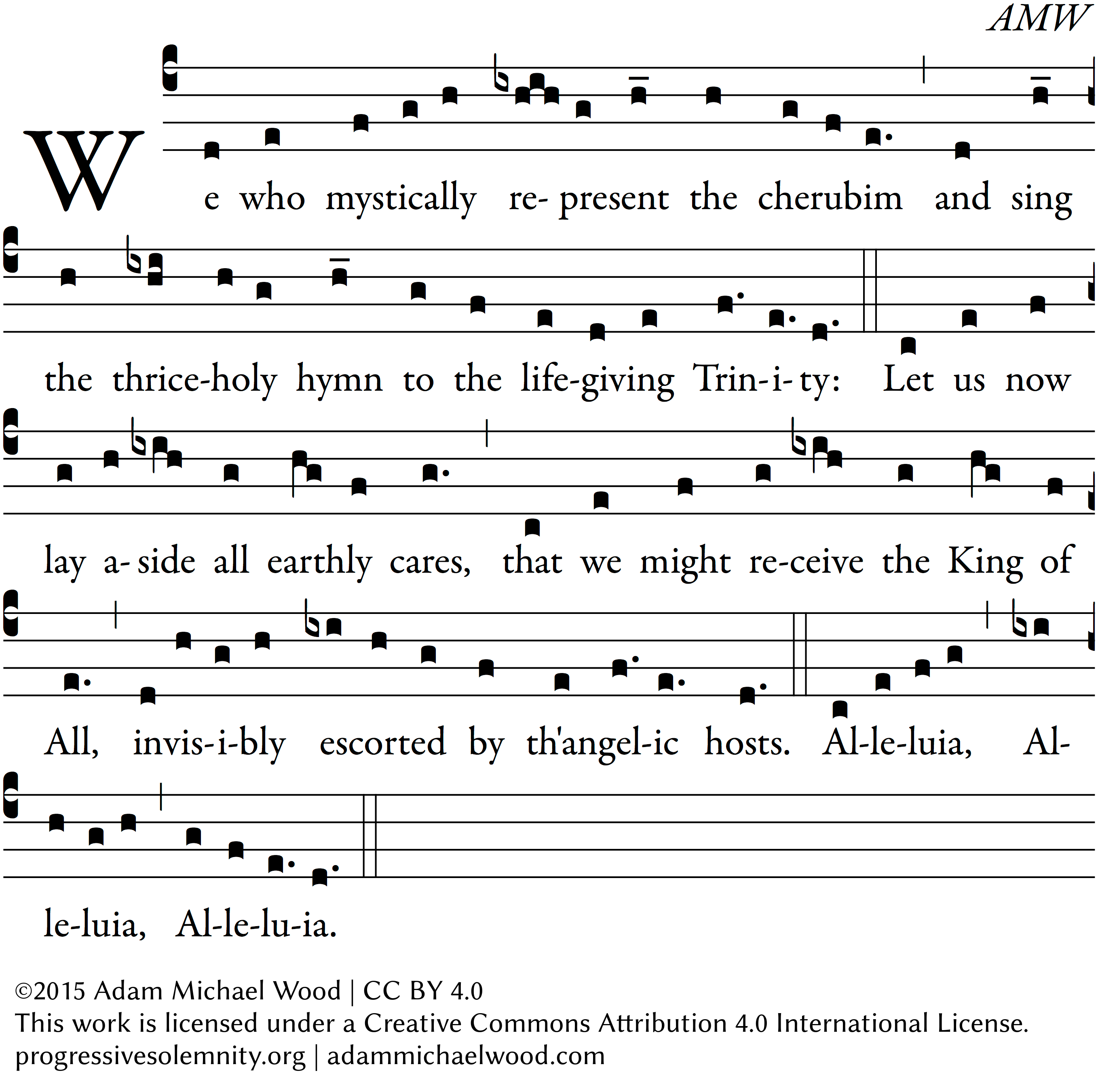

Cherubic Hymn

Audio Recording with Homophonic Drone

Audio Recording with Ison (Hummed Drone)

Files

Credits

Text

Traditional, from the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom

Tune

Adam Michael Wood

Singers

- Br. Eckhart “Chip” Camden, OSB

- Br. Kevin Gore, AF

- Br. Brendan Williams, OSB

- Adam Michael Wood

Copyright & License

© 2015 Adam Michael Wood

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Open Source Prayerbook

So far, most of the conversation about Prayerbook Revision has been focused on content. It seems that the people who have pushed for the coming revision have done so out of a concern for “updated” content (whatever that means), and most of the public conversations have been concerned with content — language, rubrics.

This makes perfect sense. The content of the prayerbook is the closest thing we have to an official statement of theology. The words of the prayers, the order of worship, and the rubrical instructions guide our weekly or daily rhythms of prayer and form the foundations of our personal and communal spirituality.

But talk of content, I think, is premature at this stage. The passionate cries for moderation coming from some, and for greater liberalization coming from others, will have been forgotten three, six, or nine years from now. What is needed is a process by which these voices — all voices — can have a real voice in the ongoing work of revision.

The resolution that was passed at the 2015 General Convention directed SCLM to “prepare a plan for the comprehensive revision” of the BCP.

If you care about the content of the next Book of Common Prayer — and you should — you should care about what this plan looks like.

Here is what I propose.

Open Source the Prayer Book

The next Book of Common Prayer should be an Open Source Prayer Book.

This cannot be work undertaken by a small committee of academics and insiders, by those with power in the institutional church, far away from the real lives of regular worshipers.

And — just as crucially — it cannot seem to be that way either.

No matter how many draft revisions or proposed texts are released, no matter how many times the SCLM calls for trial use and feedback, if the process for revision is not radically open and transparent, there will very likely be a strong sense that a new prayer book is being imposed on the church against the will of a large portion of the faithful.

The recent strong reaction against what people thought they heard in Ruth Meyers’s recent statements about Prayer Book revision are indicative of underlying fears about the content of the next Book of Common Prayer — the fear that beloved prayers will be taken away, that traditional images will be banned, that ancient statements of belief will be forgotten, that sacred metaphors will be thrown out. Underlying all these fears, I believe, is a fear of voicelessness.

The Prayer Book gives voice to our faith.

There are some for whom that voice is inadequate, a voice not their own. They — quite rightly — long for a new Prayer Book, for new language that will give words for their mouths which can match the meditations of their hearts.

Others are fearful that their voice in prayer will be taken away, that they will be required to use new and unfamiliar words, that the truth as they understand it will be abandoned.

In the discussion about BCP revision at General Convention, the Rev. Canon John Floberg, deputy from North Dakota, warned that “among the Lakota-Dakota people of the Plains, it takes on average 40 years to substantially translate the prayer book once it’s revised.” I would say that it takes at least that long — a Biblical generation — for new prayer language to become the native prayer language of a worshiping community.

The only way to ensure that the voices of all are respected in the final product of BCP revision is by making sure that all of these voices are present and respected in the process of revision.

And the only way to do that is to make the process Open Source.

What does Open Source mean?

Open Source is a methodology which has developed over the last several decades in software development. It emphasizes freedom over control, community over hierarchy, diversity over uniformity, collaboration over competition, and permission over restriction.

Practically speaking, to Open Source the next Book of Common Prayer would mean applying Open Source principles in the following, highly interrelated areas:

Open Source Process

In a typical Open Source development process, anyone can contribute in a wide variety of ways. For software development this primarily means writing code, but not exclusively that. It also means creating documentation, tutorials, and tests. It means fixing bugs as well as creating new features. It means participating in discussions. It means trying out new versions before they are formally released to the public.

To open the process of Prayer Book revision means allowing anyone to contribute in a wide variety of ways. Contributing to the texts of prayers and rubrics, participating in discussions, providing research, proofreading, trying things out.

Now… At this point, most people without Open Source experience start panicking. This seems like chaos. How do you control all of this?

Open Source is free for all, but it is not a free-for-all. Every Open Source project in existence has a relatively small group of core contributors that provide leadership and guidance, and – ultimately – decide what “makes the cut” and what doesn’t. Only a few typically have “commit privileges.”

The difference is that you have a small group of people shepherding a large community of contributors, rather than a small group of people doing all the work and making all the decisions in private. In that way, Open Source development mirrors best practices in congregational leadership, rather than the outdated model wherein the pastor and a small group of insiders make all the decision and do all the work on behalf of a congregation of consumers of religion.

Open Source Technology

In order for an Open Source process to work, it must be conducted on a technical platform designed to support that process. Prayerbook revision cannot be conducted via emailed Microsoft Word documents.

The most obvious choice for such a platform is git and Github.

Git is a version control system. It makes it (relatively) easy for many different people to work on the same project at the same time, and merge their work as needed. It tracks changes and edits, allows multiple versions to exist side by side, and radically democratizes the process of collaboration.

Github provides a central hub for git-powered projects, making them publicly accessible (even to people who don’t use git), and provides a number of collaboration tools such as discussion forums, bug trackers, project wikis for documentation, and other important features.

This platform accomplishes the goal of making the process radically transparent. Every decision, every revision, every discussion, has a URL that can be linked to, a date stamp, and the name of the person responsible for accepting the commit.

Open Format

One of the most fundamental characteristics of Open Source software — the quality that gives it its name — is that the source code is open. That is to say — available, accessible, viewable, editable.

Closed source applications are provided in compiled, executable binary form. If you were to open the file up in a code editor, you’d see a bunch of gibberish numbers. The human-written source code has been compiled into a form usable by the computer, but impenetrable to humans.

When we publish books, or even PDF documents and online liturgical resources, they are usually provided in a “compiled” form. The page numbers, the fonts, the margins, the styles — all of it, not just the essential text — is embedded into the file.

Have you have ever tried copy-pasting Psalms or prayers out of the Online BCP for use in a program? How much time do you waste stripping out the page numbers, the weird formatting, and other remnants of page layout? (I do this on a regular basis, and have developed several automated tools and techniques for it, and it is still a pain.)

If the source material for the next BCP is made available as source material — that is to say, minimally formated plain text (using something like Markdown), then it would be infinitely easier for people to remix and reuse as needed.

And it can still be provided in an easy-to-use, consumable, “compiled” format. These are not mutually exclusive goods. This very blog post, for example, is available in a “compiled” format — with styling and typographical design — on the page you are currently reading. But you can also access the plain-text source code. Many, many tools are available (kramdown and Pandoc, just for examples), and new ones could be created, which would automatically compile lightly-formatted plain text source code into ready-to-publish books in a variety of formats. (This would also make it much easier to produce online versions, app versions, large-print versions, abridged versions, and translations).

Open Licensing

I am extremely sympathetic to the idea that the next Prayer Book should be a book, but I also think it is clear that the present and likely future of liturgical worship in our church involves remix, reuse, and republishing of Prayer Book material. While a single, usable pew-book should be the standard form of the liturgical text, we need to make it as easy as possible for congregations and worshiping communities (as well schools, institutes, publishing houses, and entrepreneurs) to rearrange and repackage the material in the BCP in a manner that will fit their needs.

Open formatting, discussed above, is a huge part of that. But so is Open Licensing. There should be no artificial legal hurdles to the use of Prayer Book materials by the church.

I highly commend the use of Open Source licensing such as Creative Commons for all materials created by the institutional church.

This in no way creates barriers to the inclusion of copyright texts and other work (such as music that might be included in a hymnal) — mixed license works are published all the time, just as the current hymnal contains both copyrighted and Public Domain works. If there is a strong desire to hold a monopoly over the publication of the complete, official Book of Common Prayer, that can also be accommodated within a framework that clearly places the contents into the Commons.

The Future must be Open

Episcopalians talk a good game about being progressive and democratic. We like words like “transparent” and “collaborative.” We say we believe in empowering people, and communities.

If we mean any of those things, if we are to have any integrity at all, we cannot be a church that allows a handful of well-connected insiders to set the liturgical agenda of the entire church.

If the liturgy is to become the work of the entire people of God, then the liturgical books must be — as widely as possible — the work, the ongoing work — of the entire church. If the law of prayer is the law of our belief, then the process by which we revise our prayer must reflect our beliefs about who we are, and what kind of church we are. If the next Book of Common Prayer is really going to be Common Prayer, then the common people must have a voice in its composition, and the final product must belong to the Commons.

Further Reading

-

If you are still trying to wrap your head around how a large institution like the Episcopal Church can benefit from Open Source methodology, I highly commend The Open Organization by Jim Whitehurst, CEO of Red Hat.

-

Ben Balter is an Open Source evangelist, promoting the use of Open Source technology and methodology in governments. Many of the institutional hurdles faced by government adoption of Open Source have parallels in the church.

-

David Wiley blogs about Open Content. The BCP is not a software program, and not every aspect of Open Source development applies. Open Source Content has its own set of particular issues which need to be addressed, and David does a good job of exploring these. Most of his work involves schools and universities, which have a lot of parallels to churches.

-

The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric S. Raymond is a classic book on the benefits of Open Source methodology.

-

This blog. Please subscribe (see the form up in the sidebar, or the RSS Feed). I plan to spend a lot of time over the next few years promoting the use of Open Source methodology in the process for revising the Prayer Book.

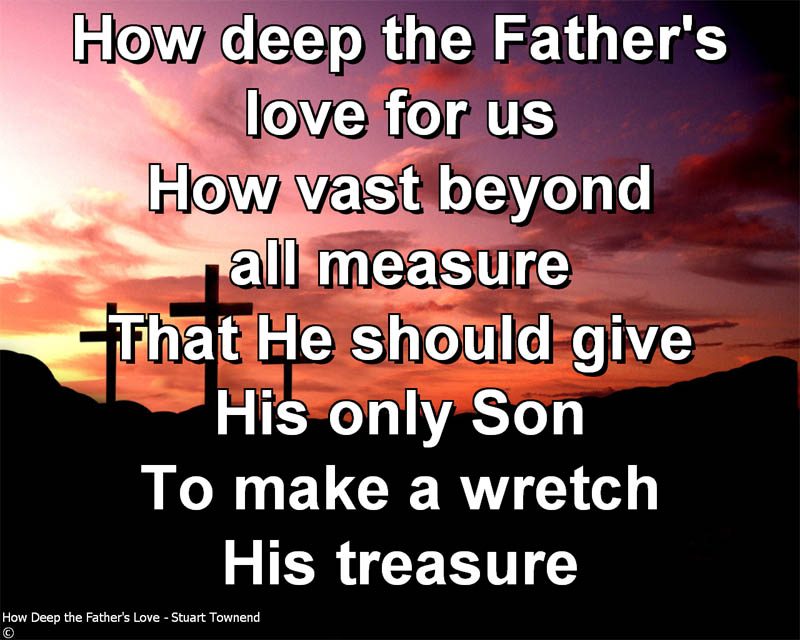

Projection Screen Hymns

A few years ago, in preparation for the diocesan convention in Fort Worth, there was a conversation about using projection screens in the liturgy (which was to be held in a convention meeting room, not a proper church building). I was not a party to this conversation, but my wife reported that someone stated that if she ever walked into an Episcopal church and saw projection screens, she would “walk out.”

Because there are people (and we all know them) who hold this kind of irrational distaste for anything that smells like innovation, it is sometimes difficult to hear the people who have legitimate concerns — practical, pastoral, and liturgical — about the use of projection screens.

The result of an inability to engage in productive conversation on topics like liturgical innovation leads to an unhealthy bifurcation where the majority remains largely insulated from change, and the minority forge ahead without thinking through how to solve the problems they create.

Whenever something is replaced by something else, there are things lost. The people obsessively concerned with that loss are irrational and should not be allowed to stand in the way of good and useful change. At the same time, those who forge ahead without concern for mitigating and dealing with loss are also irrational, and should not be allowed to run rough-shod over traditional liturgical practice.

There are definite benefits to projection screens:

- No paper waste.

- Congregational eyes up, instead of looking down.

- No one gets lost or confused by the program or prayer book.

But in the pursuit of these and other benefits, some of the benefits of the conventional paper-based solution are often lost, but which do not need to be.

A good principle should be:

Nothing that doesn’t need to be lost should be lost.

However, this is so rarely the case.

Switching from hymnals and printed worship aides to projection screens causes one unavoidable loss — the loss of a physical book to hold on to.

However, for a number of reasons (skill deficiency, laziness, lack of concern) additional losses usually occur, which do not need to:

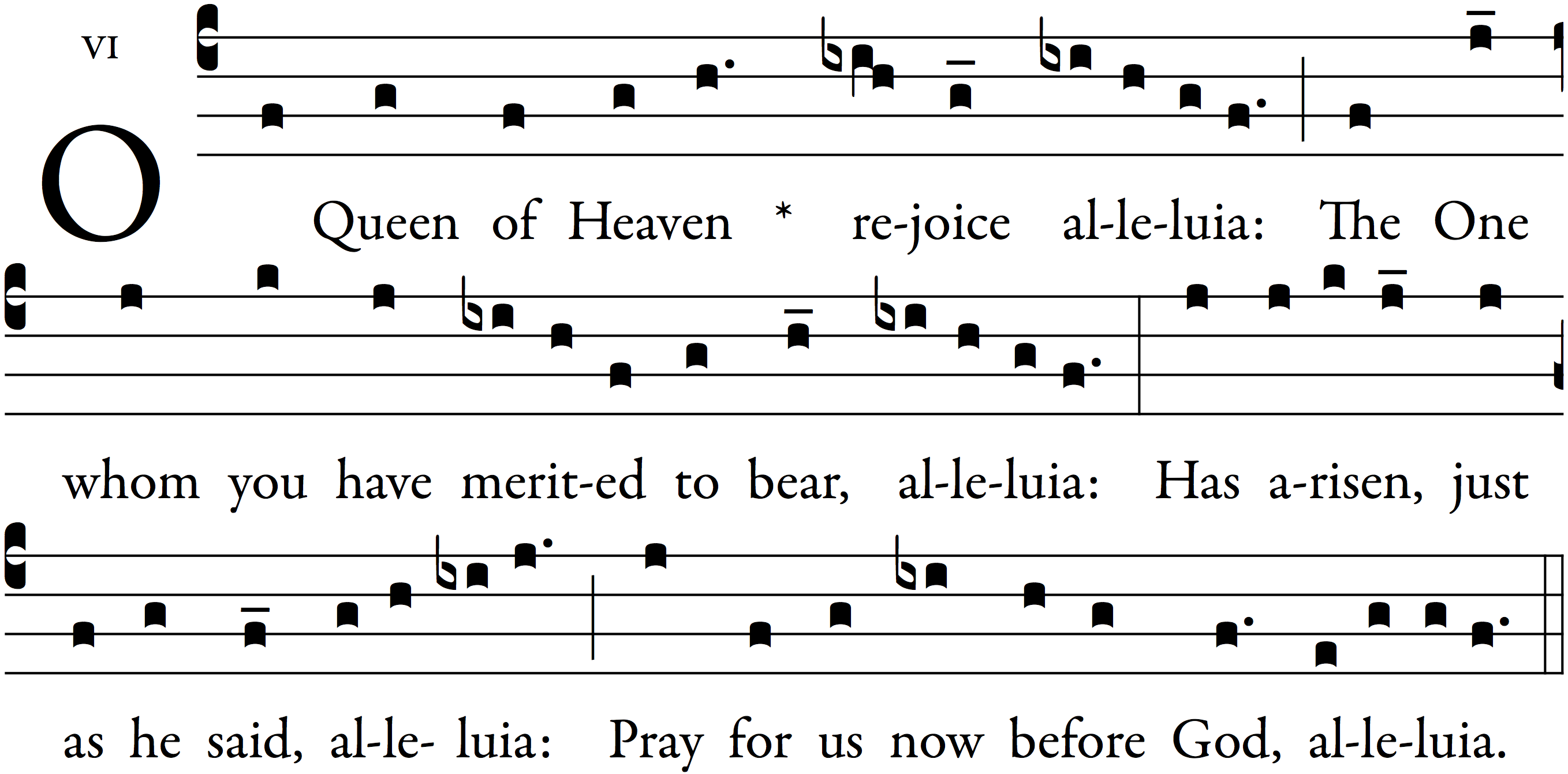

- Music notation. Many churches put only the lyrics on the projection screen.

- Dignified, traditional design. Projection screens often become cluttered with clip art and cheesy backgrounds.

Bad design is subjective, and I know plenty of people who think their gawd-awful WORDART and sentimental backgrounds are somehow helpful to the liturgy.

What is (I hope) less subjective is the extremely unfortunate situation caused by a lack of music notation. Hymn singing in church (for those who do it) is the primary way singers first learn to read music notation and sing in harmony. If we are going to retain any kind of non-consumption-based musical culture, we need to provide musical notation to our congregations. (And — oh yeah — make sure our children are in church to learn how to sing from.)

This (much too common) approach to putting songs onto projection screens has got to stop.

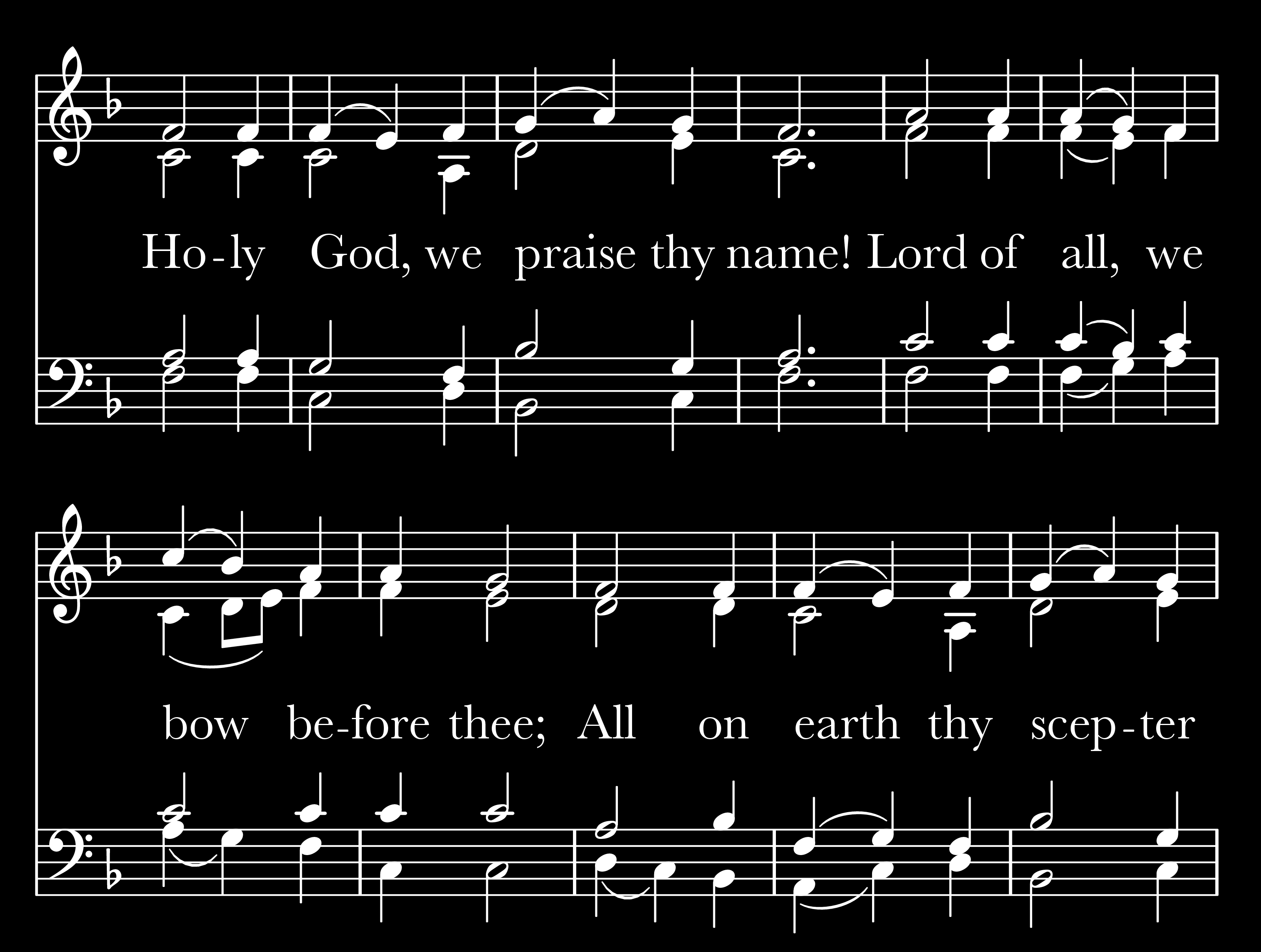

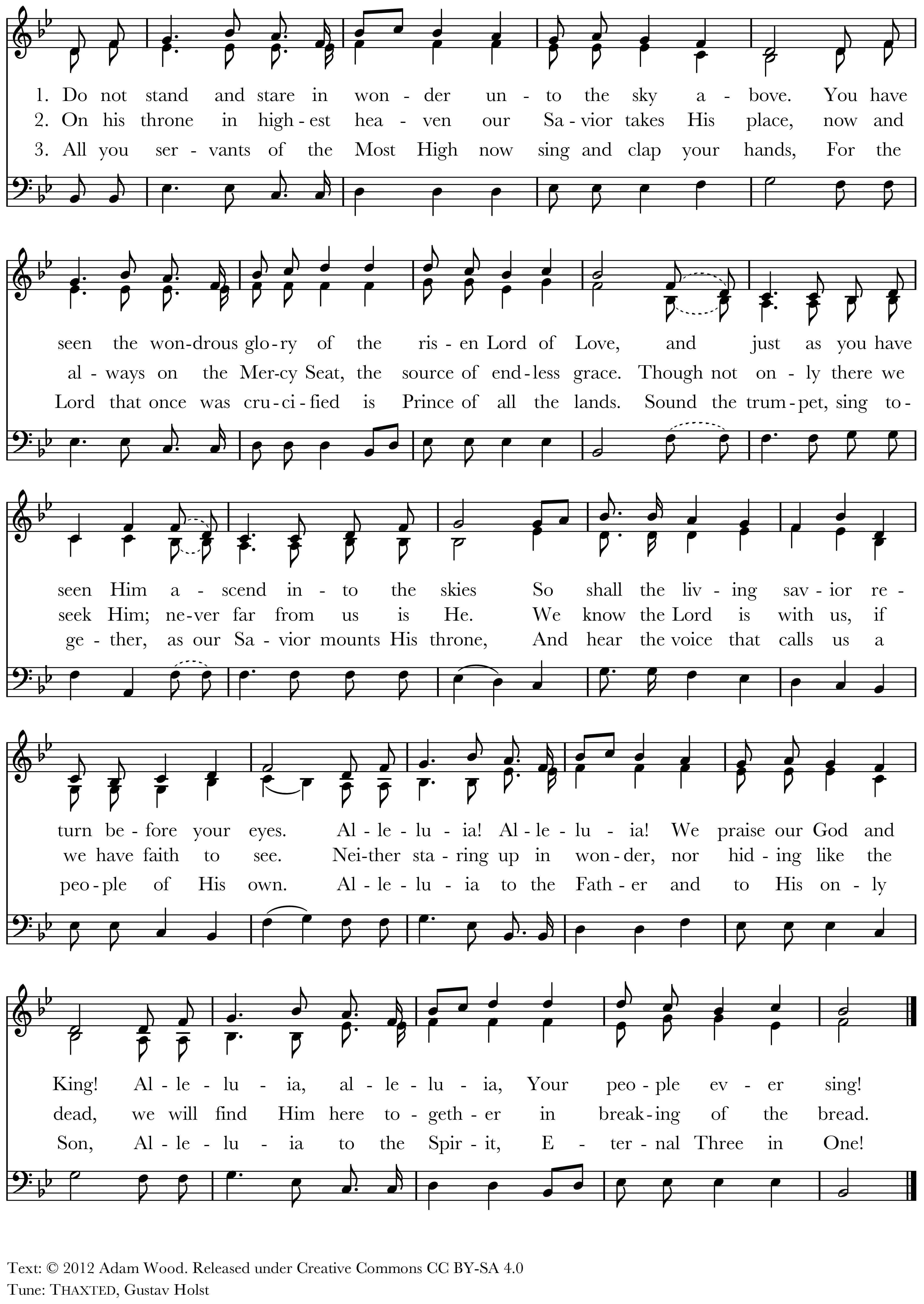

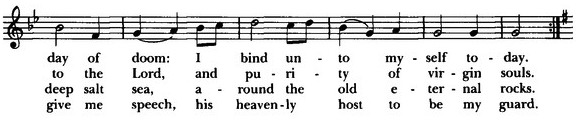

Here is a suggestion:

- All the music — four parts — is there.

- The lyrics are easy to read.

- There is no distracting artwork or cheesy font choices.

- Providing one verse at a time with music is easier to follow than in a hymnal.

- The back background makes the screen itself unobtrusive — only the content stands out, not the shape of the projection image.

This example was created entirely using Free and Open Source tools — the music was set in Lilypond and the image was cropped and color-reversed in GIMP. (You could easily use commercial software — Finale or Sibelius and Photoshop — if you wanted to.)

If you’d like to see a brief tutorial on how to use Lilypond and GIMP to create hymn screens like that, let me know in the comments. Also, be sure to subscribe.

Projection screens can also be used — with the same minimally intrusive design — for the spoken portions of the liturgy.

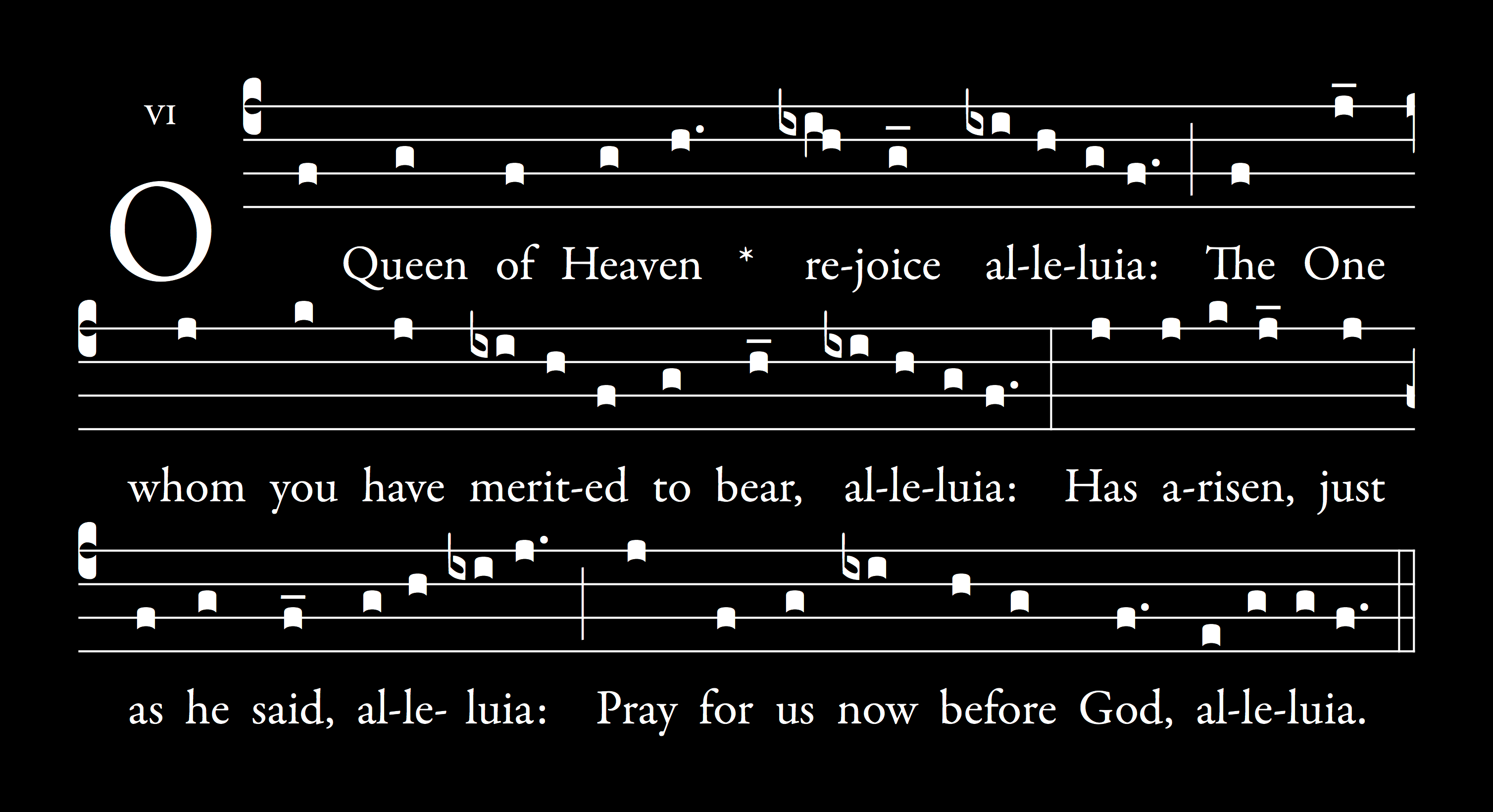

It also looks great with Gregorian chant.

Do Not Stand and Stare in Wonder

Do not stand and stare in wonder unto the sky above.

You have seen the wondrous glory of the risen Lord of Love,

and just as you have seen Him ascend into the skies

So shall the living savior return before your eyes.

Alleluia! Alleluia! We praise our God and King!

Alleluia, alleluia, Your people ever sing!

On his throne in highest heaven our Savior takes His place,

now and always on the Mercy Seat, the source of endless grace.

Though not only there we seek Him; never far from us is He.

We know the Lord is with us, if we have faith to see.

Neither staring up in wonder, nor hiding like the dead,

we will find Him here together in breaking of the bread.

All you servants of the Most High now sing and clap your hands,

For the Lord that once was crucified is Prince of all the lands.

Sound the trumpet, sing together, as our Savior mounts His throne,

And hear the voice that calls us a people of His own.

Alleluia to the Father and to His only Son,

Alleluia to the Spirit, Eternal Three in One!— Adam Michael Wood, Ascension 2012

Episcopal Church Fonts

I have long been a fan of Garamond. It’s a very popular font based on a sixteenth century design, made especially popular by Adobe’s inclusion of their version (Adobe Garamond Premier Pro) in their Creative Suite.

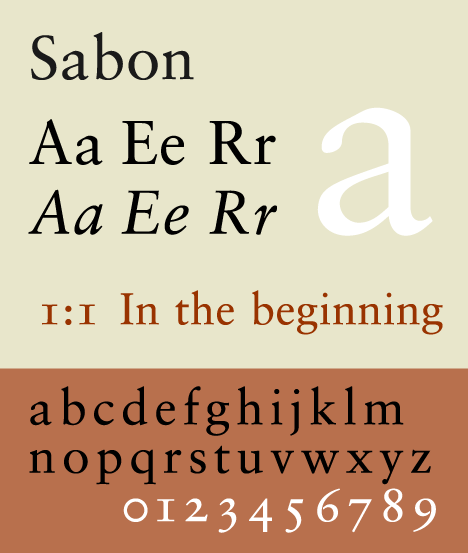

This font is especially useful for making liturgy programs (worship aids) in the Episcopal Church, because a close derivative of Garamond, called Sabon was used in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, and continues to be used for official liturgical publications.

Sabon is not widely (freely) available, but Garamond is pretty common. (And few people can tell them apart.) For this reason, I have been using Garamond in programs for years. Most of the music I’ve published has been set in Garamond.

Except that’s not right.

The Hymnal 1982 didn’t use Sabon/Garamond.

That’s Baskerville!

I have a theory about this. Okay, not a theory exactly — a handful of possible explanations.

-

Sabon seems to have been chosen at least in part because the italic, roman, and bold variants have the same horizontal size, which makes layout planning and editing much easier.

-

Sabon/Garamond is a font that hearkens back to the pre-Reformation period, while at the same time having been specifically adapted in the 1960s for modern use. From a typographical standpoint, one could hardly find a better font to express the Vatican-II-era Anglo-Catholicism that infused the text of the 1979 BCP.

-

On a related note, Sabon/Garamond is both more modern and (because of its heritage) more traditional than the very (to my eyes) Protestant/Puritan feel of the previous edition. (Below is the 1928 original and the 1940s reprint.)

-

While the 1979 Book of Common Prayer was something of a leap forward for liturgical practice, and a definite lean towards Catholic practice, the 1982 was an essentially Protestant hymnal. However much we have changed the shape of the Sunday service, the Episcopal Church’s hymn tradition is, and will always be, Protestant. (Partly because there isn’t really much of a Catholic tradition of congregational hymnody.) For this reason, a font that stays within the realm of late 19th-century book making probably felt (even if only on a subconscious level) most appropriate.

-

I am convinced that the average church-goer is much more attached to their hymnal then they are to their prayer book. Therefore, providing some visual continuity between the 1940 Hymnal and the 1982 certainly would have been prudent. The 1982 is a better-designed hymnal than the 1940, but there are clear similarities — the blue cloth cover being the most obvious. There is a close relationship between the font used in the 1940 (Bulmer) and the Baskerville of the 1982. Interestingly, that visual similarity is likely due to the fact that the designer of Bulmer, William Martin, worked in John Baskerville’s type foundry.

- Martin and Baskerville were both English. In fact, Bulmer was designed for the Shakespeare Press in 1792. This means that both the 1940 and and 1982 Hymnals use fonts designed by English Protestants in the late 18th century. The 1979 BCP uses a font designed in the 1960s by a German, based on a 16th century original designed by a French Catholic (and named after a 16th century French Catholic who lived and died in Germany). If this isn’t evidence of a Catholic-Protestant divide between Prayer Book and Hymnal, then I don’t know what is.

To top it all of, a 2012 poll found that Baskerville is the most credible font. That is — Americans are more likely to believe what they read if it is written in Baskerville, as compared with the other fonts they tested.

Discussion Questions:

-

Does Baskerville’s credibilty as a font contribute to Episcopalians’ affinity for the 1982 Hymnal?

-

Is Baskerville’s credibilty among Americans indicative of a particularly English and Protestant cultural ethos?

-

Would a change to a more “Catholic” font in a future church-wide hymnal change our musical ethos in any way?

Regina Caeli in English — O Queen of Heaven

O Queen of Heaven, rejoice! Alleluia!

The One whom you have merited to bear, Alleluia!

Has arisen just as He said. Alleluia!

Pray for us now before God. Alleluia!— Trans. AMW

Liturgy and the Need for Context

Historically authentic productions of Shakespearean plays are occasionally in and out of fashion. Recently a movement championing “original pronunciation” purports to let us hear Shakespeare’s words precisely as they would have been spoken when the plays were originally written and performed.

It is artistically irresponsible to mount a performance of a Shakespearean play — or a play from any era — without some sense of the time and culture it comes out of. Historically informed performance is extremely important if we are to be true to the stories and our own tradition.

However, the extremist point of view that advocates for a high degree of fidelity to historically authentic performance practice is ill-conceived. Setting aside the issues of historical unknowability (which is no small issue to bypass), there is a more fundamental problem with the idea of a “historically accurate” production of a venerable cultural work.

You could build a time machine and transport the original Globe, a troupe of Elizabethan actors, and old Will himself into our midst and ask them to perform for us. It would be educational. It would be thrilling. But it would not be historically authentic.

No matter how historically accurate the production of a Shakespearean play is, there is one thing you cannot reproduce: an authentic Shakespearean audience.

This is not a problem, it is simply a fact. And it is something that theatre artists are all too well aware of. But it is a reality that extends beyond theatre. It affects, of course, music, literature, and all the arts. We only need to look at an ancient building or a Renaissance painting — not a historically accurate reproduction, but the real thing — to realize that we cannot have the experience intended by the creator.

Even if we could somehow tear down the walls of contextual framing — museums, art appreciation classes, historical preservationism — even if we could remove the mediators between us and the art, there is still the reality of us.

I don’t mean to suggest that “human nature” as such has somehow changed. We have the same longings and fears, the same loves and hatreds. What we lack with the past is not essential nature but a common language.

If I shiver in near ecstasy at the sound of Gregorian chant in parallel organum over a sung drone, am I reacting to something in the music, or to the distance between that music and my personal experience?

Or, to go in the other direction of familiarity, what is it about a rolled B♭add9 chord on a warm piano that immediately lowers my blood pressure? It certainly isn’t the acoustic stability of the wave forms in a chord with two major seconds sounding on a temper-tuned instrument.

Our romantically rational explanations about the mathematical basis for the Western musical tradition tend to fall apart when applied to reality.

Does this apply to liturgy as well? I think it does.

The Vatican II-era liturgical reform sought (among other things) to return the Church’s liturgy to some pristine form from the early days of the Jesus movement. More recent scholarship indicates that many of the assumptions made about early liturgy at that point were flawed, leading to innovative practices like the inclusion of Old Testament lessons into the calendar and the present form of the Responsorial Psalm.

But the fact that they got some of the historical details wrong is hardly the point. The project is flawed even if we had accurate records. We are not first-century Christians, and a reconstructed first-century liturgy might be very informative, but is hardly authentic for us.

Unsurprisingly, the reaction against this movement — the so-called “Reform of the Reform” and the rise in attendance at Traditional Latin Mass — tends to exhibit the same flaw, just on a different time scale. Rather than looking back to the first-century, contemporary traditionalists tend to idealize the liturgical practices of some specific point in more recent history.

The most obvious example of this is the affected Baroque styling of many Extraordinary Form liturgies, combined with a compulsively scrupulous attitude toward rubricism, bordering on idolatry. But that is not the only example of aspirational historiography working in liturgical preferences. I have friends who champion liturgical forms ranging from Syriac to Sarum, and everything in between. I myself am guilty of drawing too much from an imagined Medieval worldview that probably resembles Middle Earth more than the Middle Ages.

We can recreate the Traditional Latin Mass, but we cannot recreate a traditional Catholic congregation. Yes, liturgy forms people. But the old rites grew up in the Old World, a world that also formed them. They had a different philosophical context, a different cosmological understanding, a different anthropology. Significantly, they had not lived through the liturgical reforms or had access to so many different paradigms of religious worship.

There are some who, having realized this communication gap, this difficulty in connecting the ancient liturgy to the contemporary experience, have stripped the liturgy of so many of its “accidents” (as they imagine them) that only God’s extraordinary mercy preserves the essence intact — if it is preserved at all. Calls to “communicate in a new way” too often involve little more than infantilization and secularism.

It’s worth noting that the progressive liturgical community is fond of titling workshops, books, and musical collections with some variation of “old wine in new wineskins.” It’s an evocative phrase, but it brings to my mind images of bursting wineskins and lost wine. I’m also troubled by the idea that our liturgical forms are essentially secondary containers for the content of the liturgy, which could simply be transferred to a new container without damage or loss.

On the other hand, the loss of a contemporary context within which the rites of the church make any sense has become a reason for traditionalists to double-down on their insistence that the precise forms of the Vetus Ordo be retained. “Beauty will save the world,” they say; it is hard to disagree with them.

However, the growth in popularity of traditional liturgical forms among a certain segment of the Church is not enough to prove that this approach is the right one. In many cases, the drawing in that takes place is paralleled by an exodus to more “normal” parishes.

Beauty might save the world, but it won’t save everyone in it.

Supporters point out that even if this happens, it’s only a few dissidents — that one old hippie, that liberal woman. But we worship a God who leaves the ninety-nine to seek after the one that has gone astray; a God who runs out to meet the prodigal son despite the grumblings of the faithful who remained. And it’s a lot more than one percent of the flock who have wandered far from the fold. Surely they are still our responsibility.

I can’t help but notice that so many of the people I know who thrive in traditional liturgy seem to have been especially predisposed to it. The circumstances of their lives provide the context within which these specific forms can communicate and the essence — Christ’s true presence and His eternal sacrifice — can be revealed and perceived. This predisposition is equally present in those from conservative or traditional backgrounds who have been properly schooled in classical culture and in those who have been broken and disaffected by modernity and have found a shelter from it.

But is everyone so predisposed? I’m skeptical.

Though I am convicted that all people long for the sacred, and that the sacred is present in Eucharistic liturgy in a way unlike anywhere else, I do not believe that there is any one form or style that will allow all people to access an experience of the sacred.

It is true, of course, that the sacramental and supernatural graces are freely bestowed on — and received by — all who participate in the sacrifice of the Mass, whatever their personal experience or perception of it may be. But it would be inconsistent and reductionist to rely on this aspect of God’s grace without being concerned for the social, emotional, educational, and psychological impact that the liturgy has on those present for it.

It is inconsistent because the same argument could be used to silence those who feel so displaced and irritated in typical contemporary liturgy. If the supernatural grace is all that matters, the entire concept of a liturgical movement is moot.

It is reductionist because it practically eliminates the need for sacramentality in the first place. Surely God could wave His cosmic magic wand or snap His heavenly fingers and bestow on us whatever supernatural graces or spiritual benefits He desires us to have. If our experience of physical reality is unimportant, than physical reality is also unimportant. This mode of thinking tends toward Protestant Puritanism on the one hand and New Age Ethereality on the other.

The “stuff” matters. Not just the valid matter of the species, but every detail of liturgical celebration matters. It has meaning. And if the culturally-begotten forms have meaning, then most assuredly their meaning changes when the cultural context changes.

Unfortunately, the liturgy is not so easy to translate as the framers of the Novus Ordo (or the hip parishes with projection screens) imagined. The controversy and difficulties over spoken language, where it is at least theoretically possible to assess accuracy and fidelity, point to the near impossibility of such a project in the realm of the subjective and subconscious meanings of art, music, and gesture.

What music of today speaks to us the way Gregorian Chant spoke to our ancestors? What type of clothing would communicate today what vestments communicated a thousand years ago? How can we understand anointing, or foot washing, or genuflecting when not a single one of those activities have any parallel in our secular lives?

The solution to this problem cannot be that we simply translate or adapt the liturgy to make it accessible to a modern audience. Given the intentional disposability and ironic self-awareness of contemporary cultural artifacts — including most of our language — there is little evidence to suggest that we could ever again find the kind of culturally relevant parallels that such a project of adaptation and translation should rely on. The faddish adoption of contemporary musical and architectural forms, and the clear damage that constant “progress” on this front has wrought, provides an even more convincing argument, if only the people engaged in such work could see it.

And yet such a bridge is so badly needed by so many people. The moral and spiritual poverty of this age are readily apparent, noted even by those who celebrate and work for secularization. The sense of homelessness and insecurity is pervasive, even as economic prosperity has steadily increased over the last two centuries.

What then? If we cannot go back and we should not go forward, where do we go?

I say we must go inward, to explore the richness of our tradition. Outward, to bring it to the people. Upward, in aspiring to give glory to God. Downward, to restore and reinforce our foundation.

To move inward we must continue the work that has already begun on so many fronts. Summorum Pontificum, and the parallel movements to rediscover or revive ancient liturgical practices, is the institutional cornerstone of the reclamation of our tradition. Work on historically-informed performance of Gregorian chant, as well as the translation or adaptation of our sung prayer, contributes to this effort. The trend away from Roman influence in Eastern Catholic liturgy and architecture is a part of this work, as are the efforts in the Anglican tradition who have sought for over a century to find the core of their own distinctive liturgical culture. Even in the Orthodox church, I am told, there is a seeking for what has been lost in modern Westernization.

Outward, of course, implies that we must constantly seek to engage with the world outside of ourselves. The modern era has seen a flourishing of Christian witness in the public sphere concerning issues of economic and political justice. But too often the drive to effect societal change has stripped Christian political thinking of its theological core. On the left, Catholic understandings of subsidiarity and a preference for the poor have devolved into state-socialism and welfare addiction; on the right, the zeal to protect the sanctity of life and marriage has led to a persistent effort to goad government into defining moral truth, which it is all too happy to do. What we need, I think, is a consistent public witness to spiritual truth, grounded in a sacramental understanding of the world. I’d like to see fewer marches asking politicians to stop abortions, and more marches asking women specifically to choose life over convenience or fear.

We must go upward, seeking to glorify God in all things that we do. This is easy to say, and quite obvious, but how sincere are we in our efforts to glorify God over ourselves? It is possible, I think, that many of our well-intentioned liturgical practices do not glorify God at all, but rather ourselves, our tradition, or the institutional Church. A small community scraping together their resources to build a beautiful, traditional house of worship is an offering of love, a sacrifice that brings God true glory in this world. A wealthy diocese spending ten times that amount for a single piece of furniture is close to blasphemy.

Finally we must move downward, to build a foundation. What I mean by this is that we must create (or, if you like, restore) the context in which the liturgy can communicate.

We can neither translate everything into some contemporary idiom, nor can we simply drop an ancient liturgy into the midst of modern people.

Neither the casual English of The Message nor ancient Greek are appropriate or effective languages for most people to encounter the Word of God in scripture. Ideally, we move back and forth, between linguistic study and modern translations, combining practical “life application” reflections with deeper explorations of the history and theological significance of the text. We sing the scripture and read it at home, and break it open in sermons and Bible study. So it must be with the liturgy.

If it is true, as Odo Casel observed, that modern people are unable to perform a true act of worship, then we must engage in a process that transforms people and guides them out of modernity, out of the abyss of secularism. This work includes both catechesis and community development outside the liturgy as well as careful adaptation of the liturgy itself and the elements that surround it.

Whatever (valid) form of the liturgy you are celebrating, and in whatever language, it is not enough to simply “Say the Black, and Do the Red.” Nor is it enough to mean well and be sincere. Both literally and metaphorically, we must teach people how to sing, or else what we ask them to sing is of little consequence.

The liturgy requires a context. We must provide it.

Magazine-based Liturgy Planning

Planning music and liturgy based on some subscription program from a major publisher, without a firm grounding in the traditions of the Church, is like someone who has never eaten food preparing a multi-course meal based on a single Issue of Good House Keeping and not being able to tell the difference between recipes, advertisements, and articles that aren’t even about food.

For appetizers, first we’re going to have Jell-O Molds. Then our next course will be organizing all your laundry. We’ll then move on to 20mg of Claritin, which we’ll wash down with a cocktail of Jiffy Peanut Butter and rubber bands. Our soup and salad course is remembering famous dresses worn by the First Lady, with a side of how to talk to your children about Miley Cyrus. The main course is Tuna Helper, drizzled in melted Velveeta. For dessert, we are all going to sell each other vacuum cleaner accessories.

Delicious.

Effective Evangelization Strategies

Two effective strategies for evangelization:

- Telling people who feel safe that they should be terrified.

- Telling people who are terrified that they really are safe.

Not so effective:

- Telling people who think they’re pretty much okay that they are, in fact, pretty much okay.

Our Lady of the Front Lawn

Virgin, Full of Grace

you appear in every place.

When my faith is nearly gone,

you’re in a bathtub on a lawn.

Young People and Traditional Liturgy

If you think “young people” don’t come to your church because you have “traditional liturgy” (and, therefore, need to replace it with something more contemporary), I suggest you first examine what you think is actually going on at your parish.

Four crusty hymns played too slowly is not traditional.

Random Thoughts on Liturgical Style

Everything communicates something. Everything.

Noble simplicity and liturgical minimization are not the same thing.

Traditional beauty and Noble Simplicity are not inherently antithetical.

Minimalism and minimization are not the same thing.

Minimalism and Noble Simplicity require thoughtful absence. They cannot endure an absence of thoughtfulness.

Cheap and simple are not the same.

Neither is expense an indicator of quality.

Solemn should not be confused with sad.

But sadness is a legitimate spiritual experience.

Seriousness and joyfulness are not opposites, nor are they exclusive of each other.

Sometimes, less is more. Often, less is less.

Symbols half-done are not symbols; they are talismans and witchcraft.

One should not confuse habit with tradition.

One should not confuse tradition with Tradition.

“It has always been done this way” is either the exact reason to keep doing something, or the exact reason to stop doing it.

“It’s never been done before” has a similar quality.

Black is the new black. It is also the old black.

Nobody expects it

Did you hear about the guy who didn’t realize Ash Wednesday services would be bilingual?

He wasn’t expecting a Spanish imposition!